Design Diary #3: Playtesting and Feedback

Refining a game comes with exciting ups and downs. One change can ruin the game, while another can turn a mediocre experience into something special. It’s important not to get discouraged by setbacks and to let the triumphs motivate you to keep going.

Refining a game comes with exciting ups and downs. One change can ruin the game, while another can turn a mediocre experience into something special. It’s important not to get discouraged by setbacks and to let the triumphs motivate you to keep going.

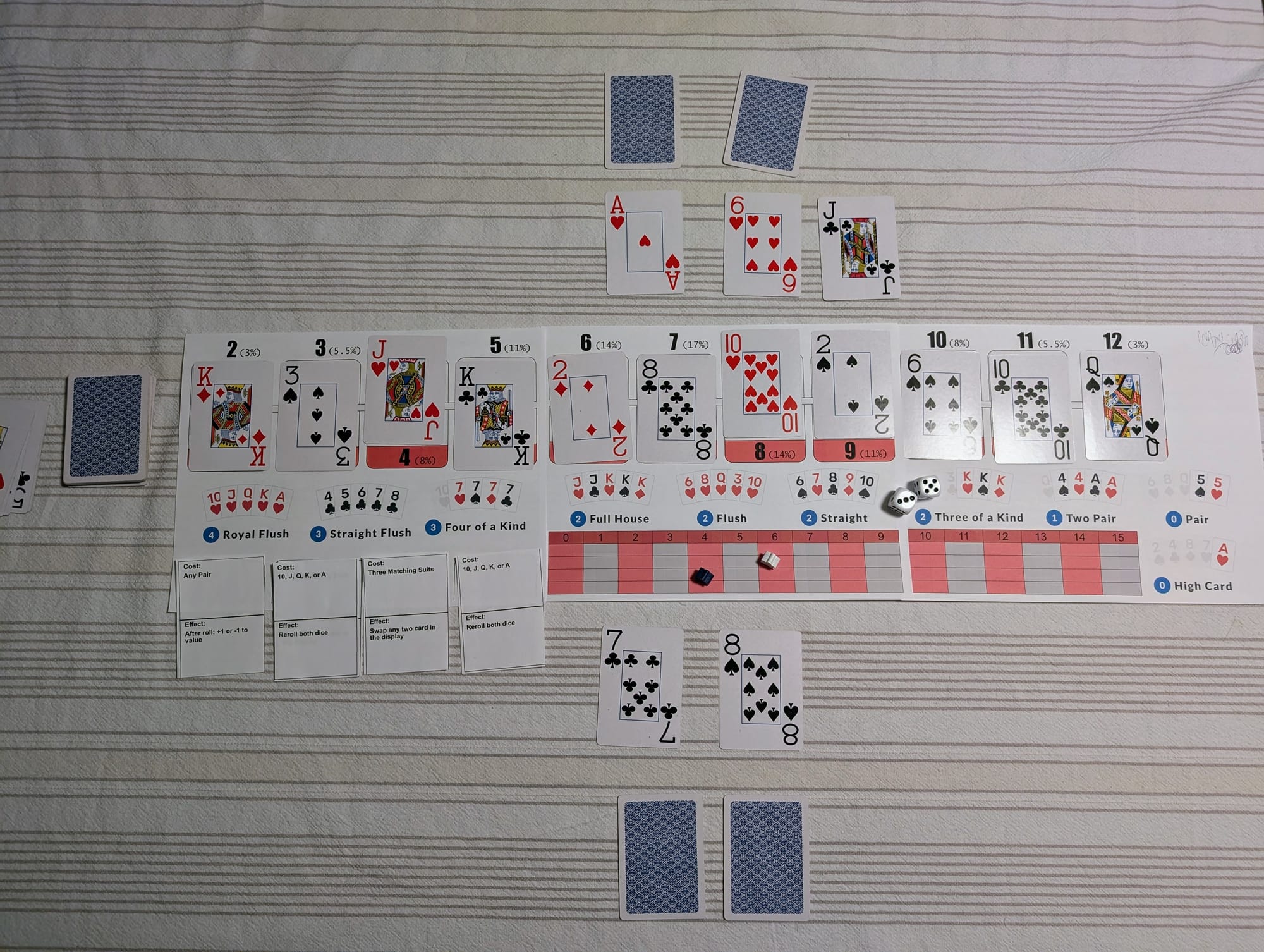

A quick summary of my still-unnamed dice-rolling poker game: Players take turns rolling dice and taking cards from the matching slot to build poker hands and score points at the end of the round. If players roll the same number twice in one turn, they get nothing.

I had just finished updating the playmat and rules, I had added new ability cards, and my partner once again offered to playtest with me.

Playtest #3

We jumped right in, and I explained the new rules. About three turns in, she asked again how she could acquire the ability card on the bottom left of the playmat.

"Spend your discarded cards to take one," I reminded her.

She laughed, then gave me some brutally honest feedback: "This is too much, and too complicated."

A bit of a setback. The ability cards, which I really liked conceptually, did not go over well. I agreed—they didn’t flow well.

In Jeremy Holcom's The White Box Essays, he writes about the ratio of fun to complexity. Every decision to add a new mechanic to the game can either increase or decrease fun while also increasing complexity. If a change adds more complexity than fun, it may not be worth it. Unfortunately, complexity and fun aren’t quantifiable, so there’s no perfect mathematical equation to measure this.

The ability cards I had added to the game certainly increased complexity, but I don’t think they added any fun. So, it was an easy decision to remove them—for now.

Talk it through

After a playtest, it’s important to talk through the player’s thoughts. It’s usually best to let others speak first before asking questions or giving your own opinions—this way, you don’t unintentionally influence their responses.

After years in software development, I’ve had plenty of experience with people calling my work bad, terrible, or confusing. There are better ways to give feedback, of course, but you often can’t choose your peers. That experience has prepared me to gather honest feedback without taking it personally.

If you can, encourage people to be honest and try not to get defensive. Learning what doesn’t work in your game is just as important as finding what does. That said, keep in mind that everyone has different tastes—your grandma may not be the biggest fan of the next big collectible card game, and your heavy-strategy-gamer friend might scoff at social party games.

If play testers didn’t like something, ask why. Maybe even ask what emotion it made them feel. Someone who felt bored versus someone who felt frustrated will give you two very different clues about what needs to change in your game.

What I learned

The Bad:

- The ability cards were too complicated to acquire.

The Good:

- The playmat made the game more readable.

- More concrete rules and a clearer scoring mechanism created a proper game structure that worked.

While reflecting on the playtest, I realized something was missing: secret information.

The key sources of excitement in poker come from three places: private cards, betting, and the reveal of new cards. I wanted to reintroduce the hidden-information aspect so players had to guess what others had. I also needed to figure out what to do with all the discarded cards.

I quickly made some changes, and we played another round:

- Each player is dealt two face-down cards at the start of the round. These cards can’t be discarded.

- Players can have up to five face-up cards.

- When discarding cards, if the discarded hand is worth points, the player may claim those points.

I wanted to incentivize rolling to build hands that could be discarded for points mid-round.

Playtest #4

Playing again with the new rules didn’t change too much. A few points were scored by discarding. End-of-round scoring was still determined by the usual poker hand types: Full House, Flush, or Straight.

The hidden information was interesting, but it didn’t lead to any particularly exciting moments. However, gameplay was getting smoother. Racing to the end of the score track was fun—whoever was behind was incentivized to go for highly risky rolls to try and land one last big hand.

There was another standout problem: If I wanted my game to support four players, there wouldn’t be enough cards.

If each player is allowed seven cards and there are 11 cards on the board:

11 + (4 × 7) = 39

A standard deck has 52 cards, leaving only 13 cards in the deck.

Assuming no one discards cards and everyone has full hands, we’d run out of cards very quickly.

How 7 Card Stud Solves Running Out Of Cards

Even 7-Card Stud, which deals up to seven cards per player, usually relies on players folding to prevent running out of cards. With eight players, if they all make it to the final round, there aren’t enough cards to go around. The solution in that game? A community card—a face-up card that all players may use as part of their hand. Anyone familiar with the popular Texas Hold ’Em variant of poker is familiar with these community cards.

We called it a night on playtesting, and I headed back to my favorite place to design games... the shower.

Prototype Files:

I include protype files relevant to this blog post so you can see the inner workings of ongoing designs or even try the game at this early stage. I often use the Affinity tool suite for digital workflows.

Additional Components Required:

- Standard 52 card deck

- 2 dice

- a score tracking token per player